6. The Arm¶

The Arm likewise is not in every part of equal force and swiftness, but differs in every bowing thereof, that is to say in the wrist, in the elbow and in the shoulder: for the blows of the wrist as they are more swift, so they are less strong: And the other two, as they are more strong, so they are more slow, because they perform a great compass. Therefore by my counsel, he that would deliver an edgeblow shall fetch no compass with his shoulder, because whilst he bears his sword far off, he gives time to the wary enemy to enter first: but he shall only use the compass of the elbow and the wrist: which as they be most swift, so are they strong in ought, if they be orderly handled.

Having before said and laid down for one the principals of this art, that the straight Line is the shortest of all others (which is most true.)It seems needful having suggested for a truth, that the blow of the point is the straight stroke, this not being simply true, I think it expedient before I wade any further, to show in what manner the blows of the point are struck circularly, and how straightly. And this I will strain myself to perform as plainly and briefly as possibly I may. Neither will I stretch so far as to reason of the blows of the edge, or how all blows are struck circularly, because it is sufficiently and clearly handled in the division of the Arm and the sword. Coming then to that which is my principal intent to handle in this place, I will show first how the arm when it strikes with the point, strikes circularly.

It is most evident, that all bodies of straight or long shape, I mean when they have a firm and immovable head or beginning, and that they move with an other like head, always of necessity in their motion, frame either a wheel of part of a circular figure. Seeing then the Arm is of like figure and shape, and is immovably fixed in the shoulder, and further moves only in that part which is beneath it, there is no doubt, but that in his motion it figures also a circle, or some part thereof. And this every man may perceive if in moving his arm, he make trial in himself.

Finding this true, as without controversy it is, it shall also be as true, that all those things which are fastened in the arm, and do move as the Arm does, must needs move circularly. This much concerning my first purpose in this Treatise.

Now I will come to my second, and will declare the reasons and ways by which a man striking with the point strikes straightly. And I say, that whensoever the sword is moved by the only motion of the Arm, it must always of necessity frame a circle by the reasons before alleged. But if it happen, as in a manner it does always, that the arm in his motion makes a circle upwards, and the hand moving in the wrist frame a part of a circle downwards the it will come to pass, that the sword being moved by two contrary motions in going forwards strikes straightly.

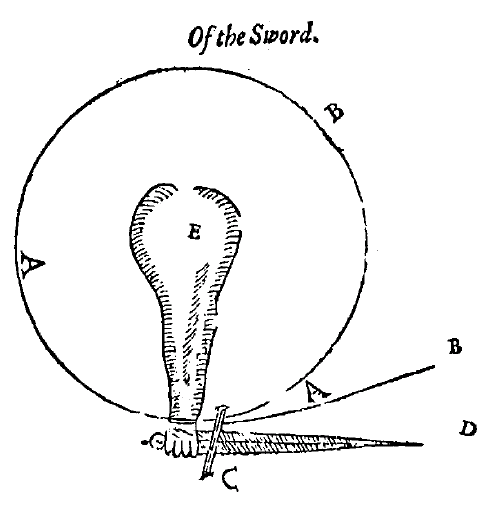

But to the intent that this may be more plainly perceived, I have framed this present figure for the better understanding whereof it is to be known, that as the arm in his motion carries the sword with it, and is the occasion that being forced by the said motion, the sword frames a circle upwards, So the hand moving itself in the wrist, may either lift up the point of the sword upwards or abase it downwards. So that if the hand do so much let fall the point, as the arm does lift up the handle, it comes to pass that the swords point thrusts directly at an other prick or point than that it respects.

Wherefore let A.B. be the circle which is framed by the motion of the arm: which arm, if ( as it carries with it the sword in his motion ) it would strike at the point D. it should be constrained through his motion to strike at point B. And from hence proceeds the difficulty of thrusting or striking with the point. If it therefore the arm would strike directly at the point D. it is necessary that as much as it lifts the handle upwards, the hand and wrist do move itself circularly downward, making this circle AC and carrying with it the point of the sword down-wards, of force it strikes at the point D. And this would not so come to pass, if with the only motion of the arm, a man should thrust forth the sword, considering the arm moves only above the center C.

Therefore seeing by this discourse it is manifest that the blow of the point, or a thrust, cannot be delivered by one simple motion directly made, but by two circular motions, the one of the Arm the other of the hand, I will hence forward in all this work term this blow the blow of the straight Line. Which considering the reasons before alleged, shall breed no inconvenience at all. Most great is the care and considerations which the paces or footsteps require in this exercise, because from them in a manner more than from any other thing springs all offense and Defense. And the body likewise ought with all diligence to be kept firm and stable, turned towards the enemy, rather with the right shoulder, than with the breast. And that because a man ought to make himself as small a mark to the enemy as possible. And if he be occasioned to bend his body any way, he must bend it rather backwards than forwards, to the end that it be far off from danger, considering the body can never greatly move itself any other way more than that and that same way the head may not move being a member of so great importance.

Therefore when a man strikes, either his feet or his arm are thrust forwards, as at that instant it shall make best for his advantage. For when it happens that he may strongly offend his enemy without the increase of a pace, he must use his arm only to perform the same, bearing his body always as much as he may and is required, firm and immovable.

For this reason I commend not their manner of fight, who continually as they fight, make themselves to show sometimes a little, sometimes great, sometimes wresting themselves on this side, sometimes on that side, much like the moving of snails. For as all these are motions, so can they not be accomplished in one time, for if when they bear their bodies low, they would strike aloft, or force they must raise themselves, and in that time they may be struck. So in like manner when their bodies are writhed this way or that way.

Therefore let every man stand in that order, which I have first declared, straining himself to the uttermost of his power, when he would either strike or defend, to perform the same not in two times or in two motions, but rather in half a time or motion, if it were possible.

As concerning the motion of the feet, from which grow great occasions aswell of offense as Defense, I say and have seen by diverse examples that as by the knowledge of their orderly and discreet motion, aswell in the Lists as in common frays, there has been obtained honorable victory, so their busy and unruly motion have been occasion of shameful hurts and spoils. And because I cannot lay down a certain measure of motion, considering the difference between man and man, some being of great and some of little stature: for to some it is commodious to make his pace the length of an arm, and to other some half the length or more. Therefore I advertise every man in all his wards to frame a reasonable pace, in such sort that if he would step forward to strike, he lengthen or increase one foot, and if he would defend himself, he withdraw as much, without peril of falling.

And because the feet in this exercise do move in diverse manners, it shall be good that I show the name of every motion, to the end that using those names through all this work, they may the better be understood.

It is to be known that the feet move either straightly, either circularly: If straightly, then either forwards or backwards: but when they move directly forwards, they frame either a half or a whole pace. By whole pace is understood, when the foot is carried from behind forwards, keeping steadfast the forefoot. And this pace is sometimes made straight, sometimes crooked. By straight is meant when it is done in a straight line, but this does seldom happen. By crooked or slope pace is understood, when the hindfoot is brought also forwards, but yet a thwart or crossing: and as it goes forwards, it carries the body with it, out of the straight line, where the blow is given.

The like is meant by the pace that is made directly backwards: but this back pace is framed more often straight than crooked. Now the middle of these back and fore paces, I will term the half pace: and that is, when the hindfoot being brought near the forefoot, does even there rest: or when from thence the same foot goes forwards. And likewise when the forefoot is gathered into the hindfoot, and there does rest, and then retires itself from hence backwards. These half paces are much used, both straight and crooked, forwards and backwards, straight and crooked. Circular paces, are not otherwise used than in half paces, and they are made thus: When one has framed his pace, he must fetch a compass with his hind foot or fore foot, on the right or left side: so that circular paces are made either when the hindfoot standing fast behind, does afterwards move itself on the right or left side, or when the forefoot being settled before does move likewise on the right or left side: with all these sort of paces a man may move every way both forwards and backwards.